The Germ Hypothesis Part 2: Koch’s Crisis

In the first part of this investigation into the germ hypothesis, we established what exactly a hypothesis is supposed to be in regard to natural science, which is a proposed explanation for an observed natural phenomenon. We briefly touched on what led to Louis Pasteur conjuring up his explanation of disease through germs with his plagiarized work on fermentation that he lifted from Antoine Bechamp. We also examined the experimental evidence that he produced for both chicken cholera and rabies in order to see if his germ hypothesis was ever scientifically proven and validated. What became clear upon investigating was that Pasteur’s experiments did not reflect his hypotheses for how the germs were supposed to invade a host in order to cause disease as “seen” in nature, thus invalidating his results. On top of that, Pasteur also misinterpreted what he was working with in regard to chicken cholera, and he was unsuccessful in isolating any microbe as the causative agent for rabies, further invalidating those experiments as he had no valid independent variable (assumed causative agent) that he was working with. There were also issues with the vaccines that were produced by Pasteur, with his chicken cholera vaccine determined to be ineffective while his rabies vaccine was linked to causing the very disease it was supposed to prevent.

Regardless, Pasteur is regularly regarded as a bona-fide hero and a scientific savant, given such titles as “the Father of Microbiology,” “the Father of Immunology,” “the Father of Bacteriology,” etc. He is considered a savior for taking old ideas, dusting them off, and then selling them back to the public as his own. However, while Pasteur is credited with developing and popularizing the germ hypothesis, he did not “prove” that germs cause disease. According to the book Science, Medicine, and Animals published by the National Research Council and the National Academy of Sciences, that glory belongs to German physician and microbiologist Robert Koch. It is stated that the discoveries of Robert Koch led Louis Pasteur to describe how small organisms called germs could invade the body and cause disease. The book goes on to say that it was Koch who conclusively established that particular germs could cause specific diseases, and that he did so beginning with his experiments investigating anthrax. This is backed up by Hardvard University’s Curiosity Collection, which states that Koch is “credited with proving that specific germs caused anthrax, cholera, and tuberculosis.” They point out that Koch’s Postulates, the four criteria designed to establish a causal relationship between a microbe and a disease, “are fundamental to the germ theory” and that they “prove both that specific germs cause specific diseases and that disease germs transmit disease from one body to another.”

While Pasteur also believed in the idea, it is Robert Koch who is the one who is credited with developing the concept of “one pathogen for one disease.” Unsurprisingly, the Robert Koch Institute also states that it was Koch, and not Pasteur, who was “the first to prove that a micro-organism was the cause of an infectious disease.”

Thus, while it should be argued that Louis Pasteur falsified his germ hypothesis, at the very least, it can easily be said that his work, by itself, was insufficient to prove his germ hypothesis. In order to “prove” the germ hypothesis, the work of Robert Koch is considered integral due to his innovative techniques involving new staining practices that allowed for greater visualization, and his utilization of “appropriate” media to culture bacteria in a pure form. The four logical postulates that developed over the course of his work, known as Koch’s Postulates, have stood for two centuries as the “gold standard” for establishing the microbiological etiology of “infectious” disease. The postulates are considered so essential that, according to a 2015 paper by Ross and Woodyard, they are “mentioned in nearly all beginning microbiology textbooks” and “continue to be viewed as an important standard for establishing causal relationships in biomedicine.” Lester S. King, a Harvard educated medical doctor who authored many books on the history and philosophy of medicine, wrote in his 1952 paper Dr. Koch’s Postulates that Koch’s contribution was in “forging a chain of evidence which connected a specific bacterium and a given disease.” King stated that this chain was so strong and so convincing “that his principles have been exalted as ‘postulates’ and considered a model for all future work.”

As Koch’s contributions to “proving” the germ hypothesis appear to be even greater than that of Louis Pasteur, we will examine the three main contributions that he supplied to the effort, with a primary focus on his work with anthrax, followed by tuberculosis and cholera. We will inspect his experimental approach in order to see if it was reflective of anything that occurred naturally within the physical world. We will see if Koch’s experimental evidence actually fulfilled his own logical postulates for proving microbes as the cause of disease. What will be clear by the end of this investigation is that the combined efforts of both Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch were not enough to confirm the germ hypothesis, and contrary to popular belief, actually led to the falsification of the entire doctrine.

Anthrax

Finally, in 1876, Koch proved that anthrax is triggered by a single pathogen. He discovered the dormant stage of the pathogen, anthrax spores, and thus unravelled the previously unexplained chain of infection and the bacterium’s strong resistance to environmental factors. In doing so, Robert Koch was the first to prove that a micro-organism was the cause of an infectious disease.

https://www.rki.de/EN/Content/Institute/History/rk_node_en.html

Robert Koch began his investigations into anthrax in 1876 while he was a district medical officer running a clinical practice in Wöllstein. At the time, the disease was attributed to the death of 528 people and 56,000 livestock over the course of a four-year period. The prevailing hypothesis was that it was a soil-derived disease as certain pastures were said to be “dangerous” to the grazing livestock and could remain so for years. It had been reported by previous researchers, with “decisive” claims by French biologist Casimir Davaine according to Koch, that certain rod-shaped bacterium were present in the blood of the animals suffering disease, and that the disease could be transmitted by inoculating healthy animals with the blood from the diseased animals. Davaine proposed that the anthrax disease, that developed without demonstrable direct transmission in humans and animals, was due to the spread of a bacterium which he had discovered remained viable for a long time in a dried state, by air currents, insects and the like. However, as noted by Koch in his famous 1876 paper Die Ätiologie der Milzbrand-Krankheit, begründet auf die Entwicklungsgeschichte des Bacillus Anthracis, these reports were refuted by other researchers who showed conflicting results where the rod-shaped bacterium was not found within the blood after fatal injections with the bacterium, and that injections of blood without the bacterium were also able to cause the disease.

Nevertheless, these propositions put forward by Davaine were contradicted from various sides. Some researchers claimed to have achieved fatal anthrax after inoculation with bacterial blood without any bacteria being found in the blood afterwards, and conversely, vaccination with this bacteria-free blood was able to induce anthrax in which bacteria were present in the blood.

Koch noted that it had been pointed out that anthrax does not depend solely on a contagium which is spread above ground, but that the disease was undoubtedly related to soil conditions, stating that it was “more significant in wet years and is mainly concentrated in the months of August and September, when the ground heat curve reaches its peak.” He went on to say that “these conditions cannot be explained by Davaine’s assumption, and their inadequacy has led many to deny the importance of bacteria for anthrax.” This led Koch to state that Davaine was “only partly correct” in his assumption that the bacterium was resistant to heat and other conditions, and that his own experiments would show that the bacterium altered its state based upon the environmental conditions. This was in reference to the spore-like form of the bacterium that Koch had discovered through his investigation, which he claimed was dormant and much more resistant to environmental factors than the active “vegetable” form. According to Koch, it was this spore form of the bacterium that the livestock ingested when grazing, and when it was deprived of oxygen inside the body, it would become pathogenic. Thus, it was the conditions of the environment that the bacterium was in that determined whether it was pathogenic or not. Koch believed that anthrax was most definitely a “soil-dependent infectious disease,” and as such, it would be logical to assume that his experiments reflected this observation and involved feeding the affected livestock the bacterium in its supposed pathogenic state. Did Koch’s experiments reflect his assumption and reproduce the disease as it supposedly occurred in nature? Let’s find out.

To begin with, Koch stated that, according to Prof. F. Cohns, “in the blood and tissue fluids of the living animal the bacilli multiply extraordinarily rapidly in the same way as observed in various other species of bacteria.” However, Koch admitted that he had not directly observed this himself but felt that it could be deduced from his experiments.

However, I have not succeeded in seeing this process directly, but it can be deduced from the inoculation experiments that I have often carried out and repeated in the following way.

To figure out how this “soil-based disease” affected livestock such as sheep, Koch resorted to experiments involving mice. He began his work by removing the spleens of “infected” carcasses and then extracted the blood. He would inject the blood into healthy mice using wood splinters as a syringe. At first, he attempted inoculating the mice by their ears or the middle of the tail, but he considered this “unsafe” as the bacterium could be removed by rubbing and licking. In other words, the mice may consume the bacterium, which is the proposed natural route of “infection.” Why this was considered “unsafe” for the mice when the purpose was to “infect” and kill them is left to the imagination, unless Koch considered it unsafe for himself to have the bacterium spread around his lab. Regardless, he eventually created wounds in the back of the tails of the mice and dropped the bacterium into the wounds.

As a very convenient and easy to have inoculation object I mostly used mice. At first I vaccinated them by the ears or in the middle of the tail, but found this method unsafe, as the animals can remove the vaccine material by rubbing and licking. Later I chose the back of the tail, where the skin is already movable and covered with long hairs. For this purpose, the mouse sitting in a covered large jar is inoculated with the tail with a long pair of tweezers and the latter pulled out of a narrow gap between the lid and the edge of the jar so that a shallow transverse incision is made in the skin of the back of the tail root and the smallest possible droplet of the bacillus-containing liquid can be introduced into the small wound.

After killing a mouse, a consecutive series of several injections would take place where new mice were inoculated with the spleen substance that had been incubated in beef serum of the mice that had recently been killed.

“…mice were inoculated several times in consecutive so that, without interruption, the following mouse was always inoculated with the spleen substance of the the mouse that had recently died of anthrax.”

While Koch claimed that he was successful in his attempts to kill the mice, the question of what actually killed them, whether it was carbonic acid in the blood or whether it was toxic cleavage products of proteins, remained unanswered. Koch preferred the latter explanation.

It would also go too far to discuss the question of the actual cause of death of the animals dying of anthrax, whether it was caused by the carbonic acid developed during the intensive growth of the bacilli in the blood or, which is more likely, by toxic cleavage products of the proteins consumed by the parasites for their nutrition.

Interestingly, it may have been a different acid that could have caused harm to the animals that Koch experimented on as he admitted to using carbolic acid (a.k.a. phenol) as a disinfectant during his experiments. Carbolic acid is a coal-tar derivative that is a toxic compound that can affect various biological systems even at low concentrations. While it was popularized by Lord Joseph Lister in the 1860s and used as an antiseptic for decades, due to its irritant and corrosive properties as well as the potential systemic toxicity, phenol is not commonly used as an antiseptic anymore. Even Lord Lister regretted having ever recommended its use and abandoned carbolic acid spray and in the 1890s stating, “I feel ashamed that I should ever have recommended it (the spray) for the purpose of destroying the microbes in the air.” Koch was known for testing carbolic acid in respect to its spore-killing powers. Could these trace amounts of carbolic acid that he knew were left over on his equipment after disinfecting them contributed to any disease in his animals that was seen in his experiments?

The small details that may be important here can be seen from the fact that in the beginning some cultures failed because I immersed all cover slips in a carbolic acid solution after use and, despite careful cleaning, traces of carbolic acid recognizable by smell sometimes remained on the jars.

In his 1879 paper Investigations into the Etiology of Traumatic Infectious Diseases, Koch stated that the spleen material must be used as the blood contained few bacilli, which is rather odd as the CDC states that the blood is used for bacterial culture and diagnosis of anthrax.

“in order to obtain constant results the material for inoculation must be taken from the spleen, because the blood of mice affected with anthrax often contains very few bacilli.”

Thus, it would appear that, according to Koch, the spleen material is the prime source of the pathogenic anthrax spores needed to kill animals experimentally. However, injecting spleen materials into mice does not reflect the hypothesis as to how natural “infection” with the bacterium would occur in nature amongst grazing livestock. Knowing this, Koch attempted to demonstrate pathogenicity using the anthrax bacterium in a way that would more closely reflect his hypothesis on how sheep would acquire the disease…by once again using mice. To reflect his hypothesized exposure route, Koch decided to feed the mice the bacterium. Nonetheless, this “natural” exposure consisted of feeding the mice the spleens of rabbits and sheep that had died of the disease, which is obviously not a natural part of the diet of a mouse. He stated that the mice ate more than their body weight in anthrax as they are “extremely voracious” eaters. Regardless of the unnatural feed and the copious amount of bacterium ingested, none of the mice became sick. As this attempt was a failure, he tried putting a spore-containing liquid in their food, which the mice once again consumed more than their body weight in with no ill effect. Rabbits were also fed spore-containing masses and remained healthy. Therefore, in these experiments, Koch had actually disproven his hypothesis that the anthrax bacterium could cause the disease upon ingestion via a more closely simulated natural “infection” route (minus the use of diseased spleens from other animals) based upon the observed natural phenomenon.

To see whether the anthrax contagium can enter the body from the alimentary canal, I first fed mice for several days with fresh spleen from rabbits and sheep that had died of anthrax. Mice are extremely voracious and eat more than their body weight in anthrax in a short time, so that considerable quantities of bacilli passed through the stomach and intestines of the test animals. But I did not succeed in infecting them in this way. I then mixed spore-containing liquid into the animals’ food. They also ate this without any disadvantage; also by feeding larger quantities of spore-containing blood, dried shortly before or years ago, did not cause anthrax in them. Rabbits, which at different times fed with spore-containing masses also remained healthy. For these two animal species, infection from the intestinal tract does not appear to be possible.

Koch seemed to realize that his evidence was inconclusive at best, saying that there was still much missing in order to understand the complete etiology of the disease, but he still tried to put on a happy face while admitting to a few glaring faults. The first thing that he acknowledged was that his experiments were all conducted on small rodents rather than the larger cattle that the disease was afflicting. However, Koch tried to reassure the reader that any differences between the animals would be unlikely. Ironically, he then contradicted himself when trying to explain away the negative results from the feeding experiments with mice and rabbits by claiming that they were not relevant to the much larger cattle due to differences in the digestive systems of the animals. He also admitted that evidence of “infection” through inhalation was still lacking.

“Let us now take a look back at the facts we have obtained so far and with their help try to determine the aetiology of anthrax. We must not conceal the fact that to construct a complete etiology still much things are missing. Above all, it should not be forgotten that all animal experiments have been carried out on small rodents. However, it is unlikely that ruminants, the actual dwelling animals of the parasite we are concerned with, should behave very differently from rodents.”

“Furthermore, the feeding experiments with bacilli and spores in rodents with their negative results are not at all relevant for ruminants, whose entire digestive process is considerably different. Inhalation tests with spore-containing masses are still lacking.”

We can see from Koch’s initial paper on anthrax that, not only did he not prove his hypothesis that the anthrax bacterium, when ingested, caused disease, he actually falsified his hypothesis by his experiments with mice and rabbits as he was unable to show that the ingestion of anthrax spores could cause disease. The only way that Koch could cause illness was through artificial and unnatural injections in various ways into small animals and rodents using different substances that did not reflect his hypothesis based upon the observed natural phenomenon. The only accomplishment that can be claimed from his paper is the description of the pleomorphic cycle of a bacterium that can be changed due to environmental influences.

Regardless, Koch and his supporters announced that he had successfully proven the cause of the anthrax disease. Yet, despite the enthusiasm and the praise heaped upon his work, there were plenty of objections and criticisms of his anthrax paper as well as the idea that bacteria were the causes of disease. In fact, according to professor of philosophy K. Codell Carter, who translated many of Koch’s papers in English for the first time, it is clear that Koch did not convincingly prove causality within his paper.

“Moreover, in spite of what Koch himself later claimed and what is now widely believed, if one reads Koch’s paper carefully one finds remarkably little direct evidence of causation, and the evidence that one finds is not of a kind that would have persuaded his contemporaries.”

Carter went on to say that Koch had not shown that inoculating isolated bacilli caused the disease, and that he did not establish that his cultures of the bacterium were pure cultures. The work was done before Koch had developed his plating technique for colony growth and was therefore performed without having isolated pure cultures. Koch simply assumed, via microscopic examination, that if he saw no contamination that his cultures were pure. This was an argument that Carter noted Koch’s contemporaries would most certainly have found unpersuasive. Having pure cultures was what everyone at the time regarded as essential, and it is a requirement that became the central tenet of Koch’s Postulates in the following years. In fact, in 1881, Koch stated, “The pure culture is the foundation of all research on infectious disease.” However, at the time he published his paper on anthrax, Koch answered his critics by stating that the “demand that inoculated bacilli be totally removed from any associated substances that may contain dissolved disease materials,” was “impossible…No one can take seriously such an undertaking.” Thus, his work in 1876 on anthrax was lacking this core component. As he seemed more interested in describing the life cycle of the bacillus rather than proving causality with a pure culture, critics were still not convinced that Koch had proven that the bacilli were the cause of anthrax.

Carter provided even more evidence against Koch’s 1876 anthrax work as proof of causation in a separate paper that he wrote exploring the creation of Koch’s Postulates. In it, he stated that Koch provided no significant original evidence that the bacilli were either necessary or sufficient for natural anthrax, and that his work centered on artificially induced anthrax.

Koch provided no significant original evidence that bacilli were either necessary or sufficient for natural anthrax. His discussion rested almost exclusively on artificially induced anthrax in test animals. Koch mentioned that he had often examined animals that died of natural anthrax. However, of those examinations he reported only that he found bacilli in the spleen of an anthrax horse-the only horse he had examined. Koch cited earlier researchers who identified bacilli in natural cases, but he also mentioned other investigators who did not find them.

Carter pointed out that Koch knew that just because anthrax was present in an animal didn’t mean that the animal would become sick, that ingesting anthrax did not produce the disease, that some inoculation procedures did not work, and that various factors were important as to whether an exposed animal would become sick. Koch would go on to develop inoculation procedures that would always kill test animals, thus showing that the inoculation procedures were the most important factor in causing disease. However, he did not state that this was direct proof that the anthrax bacterium caused the disease.

First, he knew that the mere presence of anthrax bacilli in an animal did not ensure that it would become diseased; ingesting anthrax bacilli did not invariably induce anthrax, some inoculation procedures were unreliable, and even among exposed susceptible animals, vulnerability depended on various factors. So Koch could not claim that the bacilli alone were sufficient to cause anthrax. As we will see, in later papers Koch adopted various causal criteria that were similar to but weaker than strict sufficiency. However, in the early anthrax papers one finds no such criteria. After some early failures, Koch developed inoculation procedures that invariably induced fatal anthrax in certain test animals. But in describing his procedure, he observed only that it was important because it provided a test for the viability of bacilli cultures. Nowhere in the 1876 paper did he suggest that these inoculations, which reliably killed test animals, provided direct evidence that the bacilli were the cause of anthrax.

Thus, Carter determined that all that Koch had accomplished in his 1876 paper was showing that either bacilli or spores were necessary for artificial cases of disease. His work did not prove that the anthrax bacterium caused the disease as seen in nature. From Carter’s testimony, it is clear that Koch’s early work on anthrax wouldn’t stand up to his famous postulates that he established a few years later that are considered necessary to satisfy in order to prove a microbe causes a specific disease.

Ironically, Koch’s first foray into trying to prove the germ hypothesis with anthrax led to a bitter rivalry with Louis Pasteur, the very person credited with establishing the modern version of the hypothesis. According to Carter, Pasteur regarded Koch’s work as inconclusive, and he would later point out in a response to Koch that various other observers had, like himself, come to the same conclusion about Koch’s initial anthrax evidence. Pasteur also believed that he was the first to demonstrate causality in a paper that he published in 1877.

A few months later, in the spring of 1877, Pasteur published the first of many papers on anthrax. After insisting that Davaine had preceded Pollender in observing anthrax bacteridia, Pasteur claimed that he himself, while studying the diseases of silk worms, had been the first to identify spores and to recognize that they remained viable for long periods of time. Pasteur mentioned Koch’s paper favorably and acknowledged that Koch had been the first to trace the life cycle of the organism and to identify its spores. He pointed out that Koch’s work had not persuaded the critics that the bacilli were the cause of anthrax, however, and stated that his own goal was to provide a conclusive demonstration.

Perhaps Pasteur drew shade on Koch’s work upon hearing of Koch’s paper on the anthrax bacterium, and he felt pressured to compete in the race to find and combat new microbes in order to claim priority in the discovery process. Regardless, the initial encounter between Robert Koch and Louis Pasteur was apparently a cordial one when they met in London at the request of Lord Joseph Lister, who had invited Koch to attend the Seventh International Medical Congress held during the summer of 1881.

“Pasteur also attended the medical congress in London, where he presented a paper on his results on anthrax attenuation and the successful sheep vaccination that were conducted earlier that spring. Koch presented a laboratory demonstration on his plate technique and methods for staining bacteria. Pasteur attended this demonstration session and said with admiration, “C’est un grand progre`s, Monsieur.” This praise was a great triumph for Koch, who was 20 years younger than Pasteur.”

As the story goes, during a speech by Pasteur, the translator for Koch mistranslated a phrase from Pasteur’s speech focusing on Koch’s work, turning a phrase that meant “a collection of German work” into one that meant “German arrogance.”

This time, however, a translation problem apparently provoked Koch’s unexpectedly aggressive answer, according to a document held at the Museum of the Pasteur Institute in Paris. The problem was that the two men did not speak or understand one another’s language. Pasteur referred to published work of Koch as “recueil allemand,” meaning collection or compilation of German works. Professor Lichtheim, who sat next to Koch and was rapidly converting Pasteur’s French into German, incorrectly translated “recueil allemand” as “orgeuil allemand,” which means “German arrogance.” Not surprisingly, then, Koch angrily protested this unintended insult, while Pasteur—unaware that his innocuous phrase had, mistakenly, been turned into a stinging insult—remained preternaturally calm.”

This mistranslation set off a fiery Koch to attack Pasteur’s work on anthrax, criticizing his “attenuation” of the anthrax bacterium for vaccination, while accusing Pasteur of using impure cultures while conducting faulty inoculation studies. In fact, according to Carter, in the course of his argument, Koch insinuated that Pasteur was falsifying the results of his inoculation experiments. Both Koch and German-Swiss microbiologist Edwin Klebs criticized Pasteur for not offering any new evidence as he had only repeated the experiments that botanist Ernst Tiegel had conducted sixteen years earlier. In the 1882 response Ueber die Milzbrandimfung, Koch had very harsh things to say about Pasteur’s methods, stating that his investigations had contributed nothing to the etiology of the disease: “Only a few of Pasteur’s beliefs about anthrax are new, and they are false.” According to Carter, Koch felt that Pasteur’s experiments were “worthless and naive,” and he refused to repeat an experiment of Pasteur’s that he described as a “useless experiment.” Koch accused Pasteur of confusing anthrax bacilli with other similar organisms, and he pointed out that, contrary to Pasteur’s claim of priority (something Pasteur was infamous for), his own work on anthrax had proceeded Pasteur’s by a year.

Pasteur believes that he has discovered the etiology of anthrax. This etiology could only be established by identifying the enduring forms of anthrax bacilli, the conditions of their origin, their characteristics, and their relation to soil and water. Although I have no interest in priority disputes, these matters are so obvious that I cannot ignore them. I can only answer Pasteur’s claims by referring to my publication of 1876 that describes the generation of anthrax spores and their relation to the etiology of anthrax. Pasteur’s first work on anthrax was published one year later, in 1877. This requires no further comment.

While challenging Pasteur’s work on rabies, Koch criticized the defective methods that Pasteur had used in the study of both rabies and anthrax, which ironically could be pointed right back at himself as Koch had also failed to use pure cultures and suitable test animals.

Thus, because of the lack of microscopic investigation, because of the use of impure substances, and because he used unsuitable test animals. Pasteur’s method must be rejected as defective. It cannot lead to conclusive results. One cannot criticize Pasteur himself for his interpretation of his results. His biases got the better of him, and he reported wonderful things about the diseases found in his test animals and about the remains in their corpses. After all, Pasteur is not a physician, and one cannot expect him to make sound judgments about pathological processes and the symptoms of diseases.

Koch also criticized Pasteur for his secrecy regarding his experimental methods, noting that Pasteur kept them hidden, ensuring that his work was unable to be reproduced and verified independently by other researchers.

Pasteur deserves criticism not only for his defective methods, but also for the way in which he has publicized his investigations. In industry it may be permissible or even necessary to keep secret the procedures that lead to a discovery. However, in science different customs prevail. Anyone who expects to be accepted in the scientific community must publish his methods, so that everyone is able to test the accuracy of his claims. Pasteur has not met this obligation. Even in his publications on chicken cholera, he attempted to keep secret his method of reducing virulence. Only pressure from [Gabriel Constant] Colin induced him to reveal his methods. The same was true of his attenuation of the anthrax virus. As yet, Pasteur’s publications on the preparation of the two inoculation materials are so imperfect that it is impossible to repeat his experiments and to test his results. Having adopted such a procedure, Pasteur cannot complain if he encounters mistrust and sharp criticism in scientific circles. Science makes its methods public without reservation. In this respect, Toussaint and [Augusta] Chauveau, who are working in the same area, are a pleasing contrast to Pasteur.

Koch took aim at Pasteur’s anthrax vaccine, stating that “all what we heard was some completely useless data” and that just pointing out how many animals withstood inoculation compared to how many died did not prove that the surviving animals were therefore “immune.” Pasteur had failed to demonstrate “immunity,” and reports were accumulating that his vaccine had failed to achieve the desired goal, while Pasteur “completely ignored the many failures that were known to him.”

“According to Pasteur, in France by the beginning of September, 400,000 sheep and 40,000 cattle had been inoculated. Pasteur estimated losses to be about three sheep per thousand and about 0.5 cattle per thousand. Of course, I will not challenge these figures, but it is necessary for them to be accompanied by a commentary. From these figures, one knows only that a relatively large number of animals withstood inoculation. However, Pasteur says nothing about our main concern, namely whether the inoculations fulfilled their purpose and made the animals immune. The value of preventive inoculations is determined by how many animals have been immunized. What would one have said of Jenner if he could claim no advantage for inoculation except that of thousands of inoculated children, only such-and-such a percentage died? Certainly, nothing would do more to insure acceptance of anthrax inoculations than knowing that thousands of animals have been protected against anthrax. As yet, Pasteur has not been able to show this. On the contrary, complaints about failures of the inoculation are accumulating, and its weaknesses are becoming ever more obvious.”

“On the other hand, it is very surprising that Pasteur, who conscientiously included the animals inoculated with weak vaccine in order to arrive at the largest number of inoculations with the smallest number of losses, completely ignored the many failures that were known to him.”

Koch criticized Pasteur for ignoring results that were unfavorable to his experiments while only promoting results that he could use to advertise his “successes.”

Thus, Pasteur follows the tactic of communicating only favorable aspects of his experiments, and of ignoring even decisive unfavorable results. Such behavior may be appropriate for commercial advertising, but in science it must be totally rejected.

Interestingly, in his attack on the defective methods and results obtained by Pasteur, Koch stated that, unlike in his 1876 paper, he did try to reproduce the disease naturally by feeding sheep anthrax containing materials. However, there are some issues with his methods that he shared. First, the sheep were given pieces of potatoes which are not a natural part of a sheep’s diet, and potatoes are known to be toxic to sheep as they contain solanine and chaconine which can be poisonous when consumed. The most likely reason that Koch utilized potatoes is because, at the time, he used them to culture his bacterium, but they were problematic as the slices were frequently overgrown with molds. Regardless, he would feed one set of sheep with the fresh spleen of a recently deceased guinea pig that was wrapped in potatoes, and the other set of sheep were fed slices that were cultured with the spores of the bacterium. While the sheep fed the spleens survived, the others fed the cultured potatoes succumbed to disease. However, this is where the second issue occurs. The spleen is where Koch stated that the anthrax material is found. In a separate paper from 1884, he claimed that “spores are never formed within the body” and that, by taking a portion of the organs, “it was known that it was the bacilli alone that were introduced.” In other words, Koch assumed that the spleens contained no spores, but only the bacilli. However, it was demonstrated by Italian bacteriologist Giuseppe Sanarelli that anthrax spores can remain dormant in the host tissues. Thus, there is no way for Koch to be able to claim that the spleens fed to the sheep that survived were free of dormant spores. They could have easily been fed anthrax spores within the spleen materials and survived, thus once again refuting his hypothesis.

“I fed several sheep fodder that contained anthrax bacilli but no spores. A few other sheep were fed anthrax masses that contained spores. I fed the sheep by carefully placing pieces of potato into their mouths. These pieces were filled with infection matter. They were inserted so that there was no possibility of injuring the mucous membrane. Certainly a piece of potato cannot count as prickley food. Otherwise, the sheep were fed only soft hay. Thus, Pasteur’s conditions for infection were totally excluded. As a spore-free substance, we used the fresh spleen of a guinea pig that had just died of anthrax. As a substance containing spores, we used a culture of anthrax bacilli on potato that was building spores. The sheep fed with spore-free spleens remained healthy. Within a few days, the sheep fed with bacilli cultures that contained spores all died of anthrax.”

In another experiment, Koch attempted to show that sheep eating a small amount of spores would succumb to the disease. In this instance, ten sheep were given potatoes with silk threads of anthrax spores attached. Two control sheep were fed only the potatoes. Over the course of the experiment, four of the ten sheep fed the silk threads died. The two controls remained healthy. However, once again, some issues arise beyond the use of the potentially poisonous potatoes. First, the sample size is extremely small, with only ten experimental sheep and two controls. At the very least, 10 control sheep should have been used. Second, the control sheep were not fed any silk threads. In order to keep things exactly the same between the two groups, silk threads without any spores should have been utilized. Third, only four sheep died while the other six remained healthy. What accounted for 60% of the sheep fed anthrax spores remaining free of disease?

“It was, therefore, necessary to determine that natural infection could also occur from eating a small quantity of anthrax spores mixed with fodder as dust or mud from a swamp or flooding stream. For this reason, we undertook the following experiment: Each day, ten sheep were given pieces of potato to which silk threads with anthrax spores were attached. Each thread was scarcely one centimeter long. One year earlier, each thread had been impregnate with a small quantity of anthrax spores and then dried. Two sheep, which served as controls, were kept in the same stall with the other sheep, and were cared for in the same way. However, they received no threads containing spores. Four of the ten sheep died. These deaths were on the fifth, sixth, eleventh, and nineteenth days of the test. The feeding tests were then discontinued. Both control animals remained healthy. In this test, the cases of anthrax that occurred over several days and the dissection results conformed perfectly to natural anthrax. Natural infection usually–in cold weather perhaps always–occurs when fodder containing anthrax spores enters the intestine. If sheep eat fodder that contains many spores, they die after a few days; if they eat fewer spores, they die more slowly.”

While Koch may have thought that his experiments reflected a natural exposure route proving that ingesting anthrax spores resulted in disease, this was not found to be true by other researchers. In fact, it is a well known fact that “anthrax bacilli or spores in large numbers can be fed to laboratory animals without producing anthrax, whereas they are highly susceptible to cutaneous inoculation.” In other words, natural exposure routes with the spores does not result in disease, whereas unnatural artificial injections do. This was confirmed by Sanarelli in 1925, where he stated that large amounts of anthrax bacilli or spores can be ingested without illness, and even injections of blood produced no harm. In 1922, Holman tried feeding gelatin capsules with “virulent” spores to mice and guinea pigs, which also resulted in no harm, although “virulent” spores were recovered from the feces:

“Sanarelli (1925) found that large numbers of anthrax bacilli or of spores may be given by mouth to laboratory animals without infecting, and that the blood of an infected animal may be injected per anum without harm. Virulent anthrax spores enclosed in small gelatin capsules may be swallowed by mice and guinea-pigs without harm, though virulent spores can be recovered from the faeces for a week (Holman, 1922).”

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK310481/

In his 1925 paper The Pathogenesis of “Internal” or “Spontaneous” Anthrax, Sanarelli went so far as to say that, even though Koch’s views on anthrax had been generally accepted, further studies on the ingestion of anthrax spores contradicted his results, and that no one could reproduce the “intestinal anthrax mycosis” of the Koch school.

“The views of Koch have been very generally accepted, but further observations on the effects of the ingestion of anthrax bacilli or spores have given contradictory results, and the author considers that no worker has succeeded in reproducing experimentally the “intestinal anthrax mycosis ” of the Koch school.”

Thus, it can be seen that the hypothesis that animals fed anthrax spores would become sick and die of the disease was repeatedly falsified, not only by Koch, but by various independent researchers as well. In fact, how an animal contracts anthrax in nature is still considered an unknown, and it is regarded as being in the realm of a theory, i.e. an unproven assumption, rather than a scientific theory supported by a proven hypothesis. There are different explanations, but they all vary and are purely speculative.

While the above evidence shows how Koch could not prove his germ hypothesis through natural methods, we can further demonstrate the faults within his anthrax evidence by applying his very own postulates to his work.

- The microorganism must be found in abundance in all cases of those suffering from the disease, but should not be found in healthy subjects.

- Koch admitted in his paper that fatal anthrax could occur after inoculation with bacterial blood without any bacteria being found in the blood afterwards, and conversely, vaccination with this bacteria-free blood was able to induce anthrax in which bacteria were present in the blood.

- Unknown to Koch at the time, there are cases of asymptomatic anthrax as documented in a study that found that B. anthracis was recovered from the nose and pharynx of 14 of 101 healthy workers.

- The microorganism must be isolated from a diseased subject and grown in pure culture.

- As noted by Carter, Koch had not yet developed his methods for obtaining pure cultures of bacteria at the time he studied anthrax, and he only assumed that his cultures were pure.

- Koch argued against criticism that his cultures were not pure by stating that it was an impossibility, thus acknowledging that his anthrax cultures did not meet his later necessary standards.

- The cultured microorganism should cause the exact same disease when introduced into a healthy subject.

- In his 1876 paper, Koch was unsuccessful in recreating anthrax via the natural route of exposure as proposed by his hypothesis based upon the observed natural phenomenon.

- Koch was only successful in creating disease through unnatural artificial injections of impure substances.

- The microorganism must be reisolated from the inoculated, diseased experimental host and identified as being identical to the original specific causative agent.

- As he was unable to recreate the disease through natural exposure routes, it was not attempted to obtain the bacterium from the unsickened animals.

- While he was able to find the bacterium in cases where he used unnatural modes of injection, as mentioned previously, Koch noted that there were cases were the bacterium could not be found in animals that died of the disease.

In his 1882 paper criticizing Pasteur, Koch compared and contrasted his own methods with those of Pasteur. He stated that, from the start, one needed to examine “all the body parts that are altered by the disease to establish the presence of the parasites, their distribution in the diseased organs, and their relation to the body tissues.” Afterward, one could “begin to demonstrate that the organisms are pathogenic and that they are the cause of the disease. For this purpose they must be cultured pure and, after they have thereby been entirely freed from all the parts of the diseased body, they must be inoculated back into animals, preferably of the same species as those in which the disease was originally observed.” As the example of where this had been done, Koch brought up tuberculosis as the disease where he had fully satisfied his criteria. Yet, as noted by Carter, he did not actually follow these steps in identifying the cause of anthrax, and his 1876 and 1881 papers reveal that he had followed a significantly different strategy. The strategy that Koch had used in investigating anthrax not only falsified his hypothesis, it failed his own necessary criteria for proving the microbe as the cause of the disease.

Tuberculosis

“All who mix with tuberculosis patients got infected, but remained well so long as they took care of themselves and kept the soil in a condition unfavorable for the growth of the seed.”

While it is clear that Robert Koch did not prove his hypothesis regarding anthrax and that his evidence produced did not hold up to his own postulates, it was his work with tuberculosis a few years later that ultimately brought Koch fame as the “great microbe hunter.” According to Carter, it was Koch’s discovery of the TB bacterium that “probably did as much as any single accomplishment to establish the domination of the germ theory.” In fact, his TB work earned Koch the coveted Nobel Prize in 1905 for “his investigations and discoveries in relation to tuberculosis.” It is with this work that Koch formed his famous postulates that have since stood as the gold standard for proving that microbes cause disease. As I wrote about Koch’s TB evidence previously, I won’t rehash everything here. However, I do want to examine his work in relation to whether the experiments reflected a hypothesis based upon an observed natural phenomenon as well as see if he was able to satisfy his own postulates.

In order to “discover” the TB bacterium in the early 1880s, Robert Koch invented special staining procedures so that he could easily visualize the bacterium in the organs of diseased hosts. In the opening of his 1882 paper The Etiology of Tuberculosis, Koch stated that the goal of his study was the “demonstration of a foreign parasitic structure in the body which can possibly be indicted as the causal agent.” However, Koch knew that correlation does not equal causation, and thus, the “correlation between the presence of tuberculous conditions and bacilli” did “not necessarily follow that these phenomena are causally related.” However, Koch felt that “a high degree of probability for this causal relationship might be inferred from the observation that the bacilli are generally most frequent when the tuberculosis process is developing or progressing, and that they disappear when the disease becomes quiescent.” In contrast to Koch’s views, it turns out that, as noted by Dr. Herbert Snow, the bacterium is regularly absent as the disease develops, and that it is not infrequently absent from those with very advanced stages of the disease.

“The germ does not make its appearance in the sputum of consumptives until that disease has continued for several months. Dr. H. J. Loomis (Medical Record, July 29th, 1905), gives the average date of its detection at three and one-third months from inception, as fixed by the physical signs. Dr. Muthu’s extensive experience at the Mendip Sanatorium enables him to affirm that it is not infrequently absent from the expectoration of patients with very advanced disease and “extensive mischief in the lungs.” (Pulmonary Tuberculosis and Sanatorium Treatment, 1910).

Professor Middendorp denies that the bacillus exists in any tubercular nodules of recent formation, and prior to the onset of degenerative processes. Spina, Charrin, and Kuskow failed utterly to detect it in Acute Miliary Tuberculosis, wherein, were the causal theory of Koch genuine, it must needs be specially abundant.”

Oddly enough, Koch even noted that he had found cases of tuberculosis himself where the bacterium was not present, seemingly contradicting his statement of a “high degree of probability of the causal relationship.”

“In order to gain an opinion about the occurrence of tubercle bacilli in phthisis sputum I have examined repeatedly the sputum of a large series of consumptives and have found that in some of them no bacilli are present, and that, however, in approximately one-half of the cases, extraordinarily numerous bacilli are present, some of them sporogenic.”

According to Koch, in order to prove that the TB bacilli was the true cause of the disease, it would need to be isolated and removed from all contaminants and grown in a state of purity. This pure culture would then need to be introduced into a healthy animal and bring about the exact same disease.

In order to prove that tuberculosis is brought about through the penetration of the bacilli, and is a definite parasitic disease brought about by the growth and reproduction of these same bacilli, the bacilli must be isolated from the body, and cultured so long in pure culture, that they are freed from any diseased production of the animal organism which may still be adhering to the bacilli. After this, the isolated bacilli must bring about the transfer of the disease to other animals, and cause the same disease picture which can be brought about through the inoculation of healthy animals with naturally developing tubercle materials.”

Koch believed that “the most essential” source of “infection” was “the sputum of consumptives” and that this was the principal source of the transmitted disease, stating that patients with laryngeal or pulmonary tuberculosis who expectorated large quantities of bacilli were particularly “infectious.” Thus, if the hypothesized route of natural “infection” is the expulsion of large quantities of bacilli through coughing, it would be logical to try and “infect” healthy hosts through a similar manner via the route of aerosolization. However, in order to demonstrate that the bacilli caused the disease, Koch turned to guinea pigs, an animal that he admitted that he had never seen a case of natural tuberculosis in after examination of hundreds of purchased guinea pigs. The only time he noticed the disease was after the guinea pigs had been held captive for months, and the disease that was seen only occasionally resembled that as observed in humans.

From hundreds of guinea pigs that have been purchased and have occasionally been dissected and examined, I have never found a single case of tuberculosis. Spontaneous tuberculosis develops only occasionally and never before a time of three or four months after the other animals in the room have been infected with tuberculosis. In animals which have become sick from sponstaneous tuberculosis, the bronchial glands become quite swollen and full of pus, and in most cases the lungs show a large, cheesy mass with extensive decomposition in the center, so that it occasionally resembles the similar processes in the human lung….

To “infect” the guinea pigs, rather than attempt a natural exposure route through aerosolization of the bacterium, Koch injected them with his cultured bacterium into the abdomen, close to the inguinal gland. Obviously, injecting cultured bacterium into the abdomen of an animal is not how the natural route of exposure is hypothesized to occur. Interestingly, Koch noted that the animals that he inoculated experimentally developed a completely different disease. The experimentally injected animals succumbed to disease much faster and were said to have a different pathological picture, which Koch stated made it easier to tell the difference between the artificially-induced and spontaneous tuberculosis cases observed in the animals.

Animals that have been inoculated with tuberculosis show a completely different picture. The place of inoculation of the animals is in the abdomen, close to the inguinal gland. This first becomes swollen and gives an early and unmistakable indication that the inoculation has been a success. Since a larger amount of infectious material is present at the beginning, the infection progresses much faster than the spontaneous infection, and in tissue sections of these animals, the spleen and liver show more extensive changes from the tuberculosis than the lungs. Therefore it is not at all difficult to differentiate the artificially induced tuberculosis from the spontaneous tuberculosis in experimental animals.”

Koch noted that he injected the animals in various ways: either under the skin, into the peritoneal cavity, into the anterior chamber of the eye, or directly into the blood stream.

The results of a number of inoculation experiments with bacillus cultures inoculated into a large number of animals, and inoculated in different ways, all have led to the same results. Simple injections subcutaneously, or into the peritoneal cavity, or into the anterior chamber of the eye, or directly into the blood stream, have all produced tuberculosis with only one exception.

He stated that, in order to have the most success bringing about disease, the animals must be injected with the material penetrating the subcutaneous tissue, the peritoneal cavity, and the ocular chamber of the eye. If the wound was only superficial, it did not regularly result in bringing about disease.

“If one wishes to render an animal tuberculous with certainty, the infectious material must be brought into the subcutaneous tissue, into the peritoneal cavity, into the ocular chamber; in brief, into a place where the bacilli have the opportunity to propagate in a protected position and where they can focalize. Infections from superficial skin wounds not penetrating into the subcutaneous tissue, or from the cornea, are only exceptionally successful.”

Requiring deep penetration in order to successfully “infect” and cause disease was how Koch rationalized why people could regularly cut their hands around “infectious” materials and remain absolutely free of disease. He felt that “it would be hardly understandable otherwise that tuberculosis is not much more frequent than it really is, since practically everybody, particularly in densely populated places, comes more or less in contact with tuberculosis.” Koch noted that, unlike anthrax, the TB bacterium “finds the conditions for its existence only in the animal body” and not “outside of it under usual, natural conditions.” Thus, it could be said that the TB bacterium is not an outside pathogenic invader, but rather a microbe that exists only within the living organism.

It is clear, upon reading Koch’s TB paper, that he never attempted to recreate the conditions that were hypothesized from the observed natural phenomenon for how a healthy host was to become “infected.” Like Pasteur before him, Koch was more concerned with creating artificial disease that resembled what was known as tuberculosis through various unnatural injections of cultured bacterium in ways that the animals would never experience in nature. The creation of artificial disease through injection does not say anything about what occurs in nature, and it definitely does not prove that what is injected caused the disease over the invasive procedure and trauma inflicted upon the animals.

While some considered Koch’s work with tuberculosis “one of the most definitive pronouncements in medical history,” it was not accepted by everyone. In fact, as many criticized his findings, in 1883, Koch decided to respond to his critics in the paper Kritische Besprechung der gegen die Bedeutung der Tuberkelbazillen gerichteten Publikationen. Koch began by lamenting that his work had not been recognized by the “renowned representatives of pathological anatomy.” He assumed that they would read his work, but admitted that in “this assumption, however, I was mistaken. So far, at least, nothing has or such announcements should be expected in the near future.” Koch felt that his detractors were clinging to old traditions and “grasping at straws in order to save themselves from the incoming floods” of his work. He was angered by the satisfaction that they took in finding cases where the bacilli were seen in healthy people or occurring in other diseases, thus failing his first postulate.

“With what joy was the the news that tubercle bacilli were also found in the intestinal contents of healthy people or in a single case of bronchiectasis.”

In one instance, Koch tried to argue that Cramer’s findings of the TB bacterium in 20 healthy people was a case of mistaken identity, while again pointing out that this finding was rejoiced by many.

“It is easy to see how far removed Crämer’s alleged findings were from from shaking the new doctrine of tuberculosis in any way, and yet the news that the tubercle bacilli had been found in 20 healthy people was greeted like a redeeming word from all sides.”

Koch acknowledged that Dr. Rollin Gregg had sent him a paper expressing his conviction “that phthisis has its cause only in a loss of albumen in the blood,” with Koch stating that Dr. Gregg had told him that “Fibrin threads are said to occur in every tubercle and these were obviously mistakenly taken by me for bacteria.” In a reference to Max Schottelius’s findings that the clinical picture of tuberculosis varies between animal species, Koch noted that this holds true as well in anthrax, with the clinical picture varying quite differently in humans and animals, thus negating the attribution of results from animal experiments to humans as they do not reflect the disease as seen in humans.

“I would also like to remind you of the same situation with anthrax. The clinical and anatomical course of anthrax is so different in humans that without taking the same cause into account, i.e. the anthrax bacilli, one would have to make completely different clinical pictures out of it, and furthermore, the anthrax forms in humans differ quite considerably from those from those of animals and also from each other.”

While attempting to defend against the fact that people could eat meat contaminated with the TB bacterium without ill effect, Koch threw further shade on his own anthrax findings, noting, “For I know from my own experience of many cases in which anthrax meat was consumed without any harm.” Koch then took issue with German doctor Peter Dettweiler, who considered the bacilli a side effect from the disease rather than the cause of the disease. Dettweiler felt that Koch’s injection experiments proved nothing as the animals never acquired the typical tuberculosis disease. Koch stated that he believed that if one wanted to search, they could find an animal that, when inhaling the bacterium, would contract the same disease as seen in humans. However, Koch never demonstrated this himself.

“He also considers the tubercle bacilli a side effect of tuberculosis and not the cause, despite the fact that he found bacilli in 87 phthisicians almost without exception. In his opinion the vaccination results obtained with the bacilli cannot prove anything, because in animals only miliary tuberculosis and never the typical picture of phthisis is achieved.”

“I have no doubt that if one wanted to search for it, one would eventually find animal species which, after inhalation of such small quantities of tuberculous substance that they have only one or few foci of infection in the lungs, will also show the typical picture of human phthisis.”

Instead, Koch took to injecting animals in various ways with his cultured bacterium in order to claim that it was the bacterium that caused the disease. However, Koch was well aware of the fact that injecting other substances into animals, such as glass, metal, wood, etc. would also result in the tuberculosis disease. In other words, the bacilli were not necessary for the disease to occur. He also emphasized the difference between “vaccine and spontaneous tuberculosis,” once again pointing out that the artificial disease did not reflect that which occurred “naturally.”

“In infection trials, which were intended to the efficacy of the cultures, I never left the animals alive for 86 days but killed them at the end of the fourth week at the latest. Because, as is well known rabbits, whether they are vaccinated with glass, wood, metal etc. or not at all, if they are left in infected hutches long enough, they can eventually become tuberculous. I must emphasize this distinction between vaccine tuberculosis and spontaneous tuberculosis.”

This fact that injecting materials other than the tuberculosis bacterium into animals could bring about the same disease was noted by Dr. Rollin Gregg in his 1889 book Consumption: Its Cause and Nature. In it, he provided excerpts from Professor Henry Formad detailing his work with hundreds of animals that he divided into two classes: scrofulous and non-scrofulous. The rabbit and the guinea pig, commonly used by Koch, belonged to the scrofulous class. In these animals, any materials injected under the skin will result in tuberculosis. Injecting the bacterium under the skin in non-scrofulous animals (such as cats, dogs, and other larger animals) will not result in the disease, but if the injections are into the anterior chamber of the eye, the non-scrofulous animals will develop the disease. However, if other kinds of matter are introduced into the same parts of the eye, even common sand, the same disease will occur. As Dr. Gregg pointed out, these facts utterly annihilate the claim that the TB bacilli is the specific cause of the disease as any substance injected in the right way into the right animal will result in tuberculosis.

“Again, October 18, 1882, Prof. H. F. Formad, of the University of Pennsylvania, read a paper, by invitation, before the Philadelphia County Medical Society, on ” The Bacillus Tuberculosis and some Anatomical Points which Suggest the Refutation of its Etiological Relation with Tuberculosis,” published in the Philadelphia Medical Times of November 18, 1882. After stating that he had examined “microscopically the tissues of about five hundred animals” for the National Board of Health, “and also those of a similar or still larger number of various animals used by members” of his “classes in experimental pathology in the University laboratory during the last five years,” he divides all animals into two classes, the scrofulous and non-scrofulous, as follows:

“To the scrofulous class belong unquestionably the tame rabbit and guinea pig, and all animals in close confinement; while to the non-scrofulous belong the cat, dog and animals at large.”

Then he says if the scrofulous animals are inoculated, or have introduced under their skin, any kind of matter, whether tuberculous, diphtheritic or whatnot, even to “chemically clean powdered glass,” and survive the first results of the experiment, large numbers of them die of tuberculosis. But inoculating the non-scrofulous animals in the same way, that is, under the skin, even with pure tuberculous pus, will not produce tuberculosis. This class requires the introduction of the inoculating material into the peritoneum, or the anterior chamber of the eye, whether it be tuberculous pus or the so-called bacilli tuberculosis, in order to produce tubercles in them. And here, again, if other kinds of matter be introduced into the same parts, even to common sand, the results are the same as if tuberculous matter were used. This, as will be seen, utterly annihilates all claim to there being a specific cause of tubercles. His statements are so positive and unequivocal that liberal quotations are given from them, and even the whole lecture might be quoted with advantage, so important and so directly applicable is it to our subject.”

Dr. Gregg pointed out the faults in Koch’s methods, noting that he never had to use any cultures of his bacterium in order to produce the disease in animals. Koch knew that all he had to do was inject the non-scrofulous animals in the eye and the scrofulous animals anywhere he wanted to in order to create disease.

Koch has unquestionably produced tuberculosis in the peritoneum of his cats and dogs.” And he “could just as well have used some sand for inoculation, and saved his valuable cultures of the bacillus tuberculosis for inoculation into some other parts of the bodies of the non-scrofulous dogs, cats, rats, etc.”

“Why did Dr. Koch inoculate the latter named animals only in the peritoneum and anterior chamber of the eye, while scrofulous animals (rabbits and guinea pigs) he inoculated indiscriminately in any part of the body? This is a mystery. Let us try to solve it.”

Dr. Gregg went on to provide more damning statements from Professor Formad involving his work with diphtheria. Professor Formad pointed out, as also noted by Koch, that inoculating rabbits with non-tubercular and perfectly innocuous foreign material, such as pieces of glass, metal, wood, etc. followed with death from tuberculosis. Professor Formad testified that he and Dr. Wood had seen over 100 rabbits die of tuberculosis without the bacterium being injected into them and with no intention on their part of bringing about the disease. Their results were confirmed by the work of Dr. O. C. Robinson.

“The experiments on diphtheria, of Prof. H. C. Wood and myself, have shown that those rabbits which did not succumb to the disease within a few days, nearly all died of tuberculosis in the lapse of four to six weeks or more. In order to see whether the diphtheritic material acted specifically in the production of tubercle, or whether the latter was merely the result of inflammatory process, we experimented by inoculating rabbits with non-tubercular and perfectly innocuous foreign material, such as pieces of glass, metal, wood, etc. The result was, in the majority of cases, cheesy, suppurating masses at the seat of inoculation, followed in the course of a month or more by death from tuberculosis.”

“Today I can safely testify that Dr. Wood and myself have seen die of tubercular disease proper more than one hundred rabbits out of five or six hundred operated upon, without a single one of these animals having been knowingly inoculated with tubercular matter of any kind, and without any intention on our part to study tuberculosis in them. All rabbits and guinea pigs subjected to injury in any part of the body in the various experiments and surviving the immediate or acute effects of the latter, had, with only a few exceptions, but one fate, viz., to die of tuberculosis, provided they lived long enough after a traumatic interference to develop the lesion in question.”

“These facts were also particularly well brought forward by the results of a carefully conducted series of one hundred special experiments on tuberculosis, executed by Dr. O. C. Robinson, in the Pathological Laboratory of the University of Pennsylvania:”

“In non-scrofulous animals, viz., other than rabbits and guinea pigs, neither Robinson nor Wood and myself, nor any other experimenter, ever succeeded in producing tuberculosis by inoculation, unless done in the peritoneum or anterior chamber of the eye.”

Professor Formad noted that no one, including Koch, had ever produced TB in animals that were not predisposed to the disease via injections into the skin. Koch would change his method of injection knowing how to get the result that he wanted depending on the animal that he was experimenting on.

“No one, including Koch, ever produced tuberculosis in animals not predisposed to it, by inoculation into the skin, for instance. Koch’s records of his own experiments prove this, and show that whenever he desired to produce tuberculosis in the rabbit or guinea-pig by means of his bacillus, he inoculated indiscriminately into any part of the body; but if he wanted to demonstrate the effects of his parasite in the non-scrofulous animals, he promptly inoculated into the anterior chamber of the eye, or preferably into the peritoneum. After what has been explained in connection with inflammation in serous membranes, it is evident that these experiments do not prove that the bacillus is the cause of tuberculosis.”

Dr. Gregg summarized the points by Professor Formad, stating that the ability to produce tuberculosis with injections of non-tubercular substances proved that the bacilli was not the cause of the disease, and that medical men needed to stop wasting time chasing tuberculosis as a contagious disease.

“And yet, the insertion of “pieces of glass, metal, wood, etc.,” into the same parts would produce tuberculosis just as readily as would tubercular pus or the bacillus tuberculosis; while the simple insertion of the same non-tubercular materials under the skin of scrofulous animals produced identically the same results that the tubercular matter had upon that class. Could anything more positively and absolutely prove the non-specific character of tubercular matter, or the bacillus tuberculosis as an infectious agent, than this? If wood, glass, etc., produce exactly the same results as the so-called parasite of tubercles, when used in the same way, medical men had better give their time to other things than to waste it trying to prove that tuberculosis is a specific contagious disease.”

Ironically, Koch himself confirmed the non-contagious nature of tuberculosis, stating in 1884 that attempts were “made repeatedly to prove the contagious nature of phthisis, but they must be looked upon as failures, as such views have never found acceptance among scientists.” He admitted that “on the whole physicians consider phthisis a non-contagious disease, proceeding from constitutional anomalies.”

In his 1884 paper The Bacillus Tuberculosis and the Etiology of Tuberculosis-Is Consumption Contagious?, Professor Formad listed the many researchers who generated the same results, producing tuberculosis with substances other than the tuberculosis bacterium.

The following observers all refer to many or few experiments of their own, in which tuberculosis resulted from the inoculation with either innocuous substances or with specific matters other than tuberculous:

- Lebert, Atlgem. Med. Central Zeitung; 1866.

- Lebert and Wyss, Virchow’s Archiv, vol. xl, 1867.

- Empis, Report of the Paris Internat. Med Congress, 1867.

- Bunion Sanderson, British Med. Journal, 1868.

- Wilson Fox, British Med. Journal, 1868.

- Langhans, Habilitationschrift, Marburg, 1867.

- Clark, The Medical Tithes, 1867.

- Waldenburg, Die Tuberculose, etc., Berlin, 1869.

- Papillon, Nicol, and Leveran, Gaz. des Hop., 1871.

- Bernhardt, Deutsch. Arch. f. Klin. Med., 1869.

- Gerlach, Virchow’s Archiv, vol. li , 1870.

- Foulis, Glasgow Med. Journal, 1875.

- Perls, Allgemeine Pathologie, 1877.

- Grohe, Berliner Klin. Wochenschr, No. I, 1870.

- Cohnheim and Fränkel, Virchow’s Archiv, vol. xlv, 1869.

- Knauff, 4îte Versamml. Deutsch. Naturforscher, Frankfort.

- Ins. Arch f. Experim. Pathologie, vol v, 1876.

- Wolff, Virchow’s Archiv, vol. Ixvii, 1867.

- Ruppert, Virchow’s Archiv, vol. lxxii, 1878.

- Schottelius, Virchow’s Archiv, vol. lxxiii, 1878 ; ibid., xci, 1883.

- Virchow, Virchow’s Archiv, vol. lxxxii, 1880.

- Strieker, Vorlesungen über Exp. Pathologie, Wien., 1879.

- Martin, Med. Centralblatt, 1880, No. 42.

- Wood and Formad, National Board of Health Bulletin, Supplement No. 7, 1880.

- Robinson, Philadelphia Med. Times, 1881.

- Weichselbaum, Med. Centralblatt, No. 19, 1882, and Med. Jahrbücher, 1883.

- Balough, Wiener Mcdiz. Blatter, No. 49, 1882.

- Wargunin, Allg. Med. Centralblatt, April 8, 1882

- Hansell Arch. f. Ophthalmologie, vol. xxv.

As can be clearly seen from the statements by Dr. Gregg and Professor Formad, Koch’s work with the tuberculosis bacterium was essentially a smokescreen to prop up the germ “theory.” It did not matter whether Koch used a pure culture of his tuberculosis bacillus or scraps of glass, metal, sand, etc. as it was the very act of injecting foreign substances in the right way into the animals that resulted in the disease. If he had focused his work on saw dust, Koch could have made a convincing case that it was the cause of tuberculosis using his experimental injections. As his experiments did not reflect his hypothesized natural route of “infection,” Robert Koch was led astray by the pseudoscientific results that he obtained from his unnatural methods that created artificial disease in animals.

As Koch did not attempt to support his hypothesis with valid scientific evidence that reflected an observed natural phenomenon, we could say that his hypothesis, at best, remained unproven. However, when we examine whether his tuberculosis evidence satisfied the very postulates that he established, we can close the door on the hypothesis that the TB bacillus is the cause of the tuberculosis disease as it failed Koch’s criteria from the very start. The bacillus was found in healthy hosts (even by Koch himself), absent in diseased hosts, and found in cases of other diseases, thus failing the very first postulate. We now know that the bacterium is found in about one-quarter of the world’s population, and that there is only 5–10% lifetime “risk” of falling ill. Thus, the bacterium is found most often in healthy people. While Koch was able to grow a pure culture, the results obtained by the unnatural injection of the bacillus into animals, recreating the disease and showing it as the primary cause, was falsified repeatedly by many other researchers who achieved the same results without the use of the bacillus. These results nullify the evidence that Koch used to support the third and fourth postulates. In the end, Koch’s “monumental” work with TB that earned him the Nobel Prize was not so monumental, and as admitted in the comments of the reprint of his 1882 paper, his work with guinea pigs did not conclusively prove that the bacterium caused the disease in humans.

“Koch was also fortunate that the strain of tubercle bacillus that is pathogenic for humans can be transferred so readilv to guinea pigs. Without an experimental animal which showed characteristic symptoms upon inoculation with tuberculous material, his work would have been much harder. He might have cultured the organism successfully, but the actual proof that this organism was the causal agent for tuberculosis would have been much more difficult. It should be noted that in this paper he does not have a final proof that the organism he has isolated in pure culture is really the cause of human tuberculosis. This could only be done by making inoculations in humans. Since this cannot be done, we can only infer that the isolated organism causes the human disease. Such a dilemma is always with the investigator of human diseases. He must learn to live with it.”

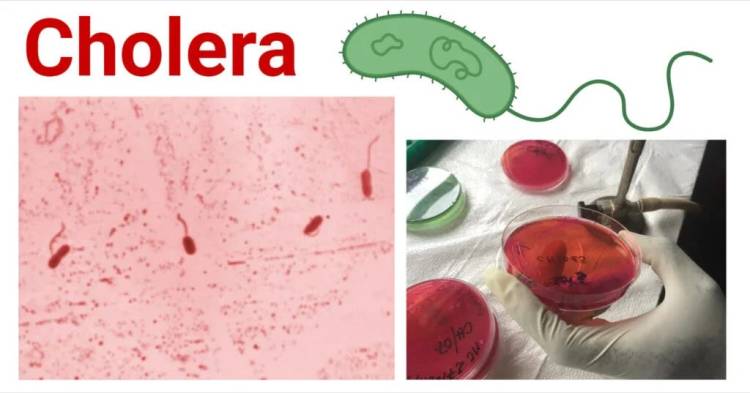

Cholera

“The only possibility of providing a direct proof that comma bacilli cause cholera is by animal experiments. One should show that cholera can be generated experimentally by comma bacilli.”

-Robert Koch

Koch, R. (1987f). Lecture cholera question [1884]. In Essays of Robert Koch. Praeger.

When Robert Koch set out to hunt down the microbe that he could claim as the cause of the symptoms of disease known as cholera, he stated that the only possibility of providing direct proof was through animal experiments that recreated the disease. It had already been hypothesized by John Snow that water that was contaminated by sewage and decaying materials was the source of the cholera outbreaks. Thus, it would be logical to conclude that drinking water containing pure cultures of the assumed causative agent would, at the very least, be the way to prove that it is the cause of the disease it is associated with. Interestingly, in the case of cholera, Koch did come close to doing something similar in his animal experiments. He actually tried to “infect” various animals through feeding them both impure and pure choleraic materials. He also resorted to subcutaneous and intravenous injection, as well as injections into the duodenum with rice-water stools and with pure cultivations of comma-bacilli. He detailed many of the methods that he utilized in his attempts to make animals sick in his 1884 paper Erste Konferenz zur Erörterung der Cholerafrage am 26. Juli 1884 in Berlin.

In this paper, Koch noted that the only way to provide direct evidence for the cholera-causing effect of the comma bacilli was through animal experiments, which, he stated, “if you follow the authors’ information, is straightforward, and should also be able to be carried out without difficulty.” However, his proceeding evidence actually showed quite a bit of difficulty. For starters, Koch admitted that they did “not actually have any reliable example of animals spontaneously contracting cholera in times of cholera.” Thus, finding a suitable test animal that could contract the disease was essentially guesswork. So, Koch decided to begin his attempts to experimentally recreate the disease using 50 mice, carrying out as many ways to “infect” them as possible. He fed the mice the feces of cholera victims as well as the contents of the intestines of corpses. He fed them both “fresh” materials as well as those that had been decomposing. However, despite repeated attempts to make the mice sick by feeding them the contents of cholera victims, they remained healthy. Koch tried to “infect” monkeys, cats, chickens, dogs and various other animals without success, even when feeding them pure cultures of the comma bacillus.

I took 50 mice with me from Berlin and carried out all possible infection experiments with them. First of all, they were fed with the faeces of cholera patients and the intestinal contents of cholera corpses. We adhered as closely as possible to the experimental procedures and not only fed them with fresh material, but also, after the fluids had been decomposed. Despite the experiments being repeated again and again with material from new cholera cases, our mice remained healthy. Experiments were then carried out on monkeys, cats, chickens, dogs and various other animals that we could get hold of, but we have never been able to achieve anything similar to the cholera process in animals. We have also carried out experiments with the cultures of comma bacilli. These were also fed in all possible stages of development.”